The complexity of law is a recurring problem faced by government bodies, judges, lawyers, jurists and, in fact, all citizens confronted with legal issues. Ideally, the application of laws should be in line with the ideals of the society that formulates them. Whether this ideal is satisfied or not depends on many factors, among which the structure of the legal system, the quantity of its resources, or the competence of law interpreters. But it also depends on the form of the laws themselves. The equilibrium of law-writing consists in remaining intelligible while accounting for the great diversity of social situations subject to legislation. It must “find an optimal balance between rigorousness and flexibility, formality and understandability, that is, between expressing authority and yet being grounded in the everyday life of those affected by it” (Höfler / Piotrowski 2011). Problems induced by excessive complexity of law are well identified in legal literature (Epstein 1995; Kades 1996; Katz / Bommarito 2013; Palmirani / Cervone 2014). They have also been drawn to public attention. Complaints about “overlegislation”, meaning the rising quantity and complexity of law, have been formulated in recent years by national media in Switzerland, partially reflecting public opinion and the views of several politicians ( e.g. Zurlinden 2013-2015c).

Our question, focused on the Swiss Federal Law, is both formal and historical. We ask whether the degree of its complexity can be measured over time and how it can be represented. How could we, for example, identify specific domains of the Federal Law in which complexity has evolved more than in others? What would this evolution mean in historical terms? In a larger scope, we ask to which extent the history of legislation can be understood with the help of quantitative methods.

Since 1848, the Swiss federal government publishes legal instruments in 3 national languages (German, French, Italian) and in 3 principal publications: the Federal Gazette, a weekly report of the Federal Council and law drafts proposed to the Federal Assembly, the legally binding Official Compilation (OC), a record of actual changes to the federal law in chronological order, updated every week; finally the trimestral Systematic compilation, in thematic order and representing the current state of federal law. Texts are partitioned in structural units (chapters, sections, articles, paragraphs, sentences and enumeration items) unequivocally identified by a reference code ( e.g. SR 313.0, art. 29, §1, al. a) equivalent for all language versions. Working with the OC allows us to observe the chronological development of law on a weekly basis.

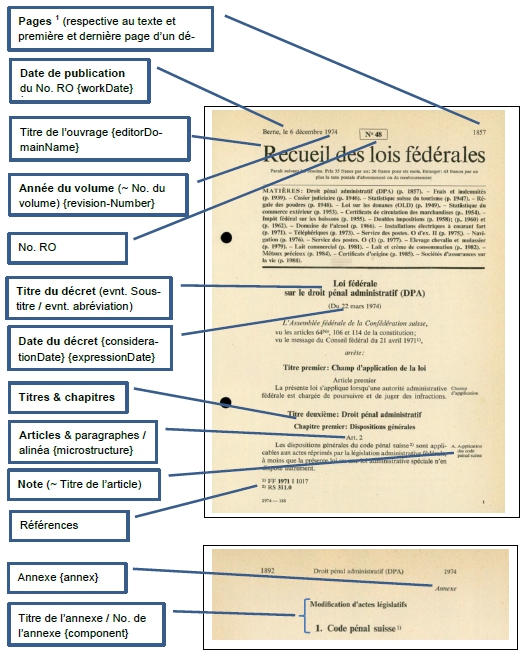

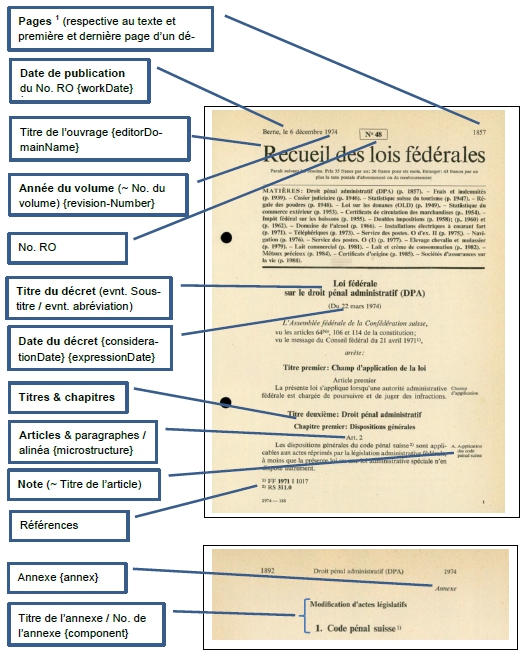

The OC is available since 1998 in digital format convertible to hierarchically structured XML by an XSLT transformation. Prior to 1998, the Swiss federal archives (SFA) dispose of paper version of the OC. This repository is currently being scanned in the scope of our project. Fields recognition (Figure 1) and OCR is applied to obtain, here also, structured XML (Figure 2).

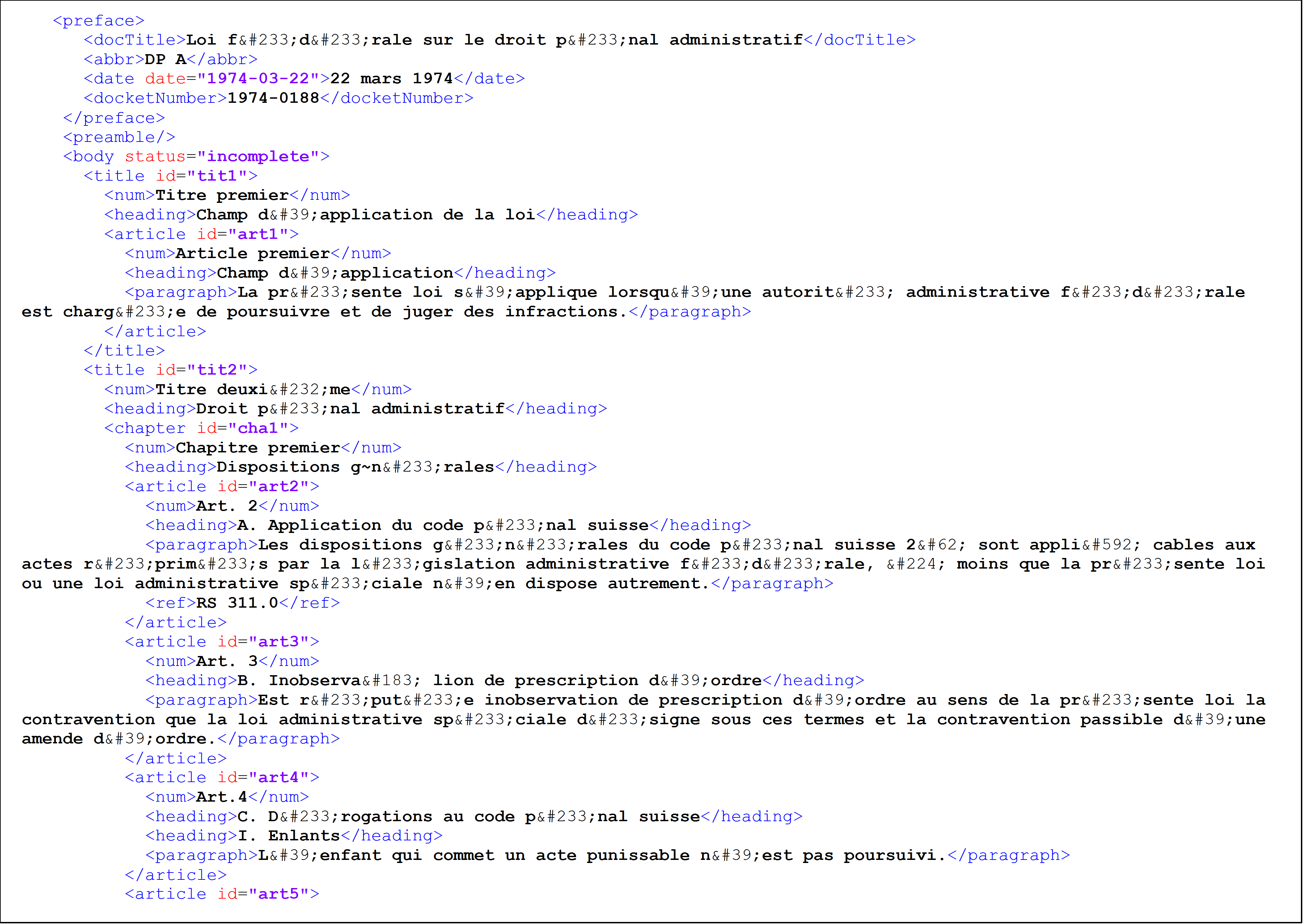

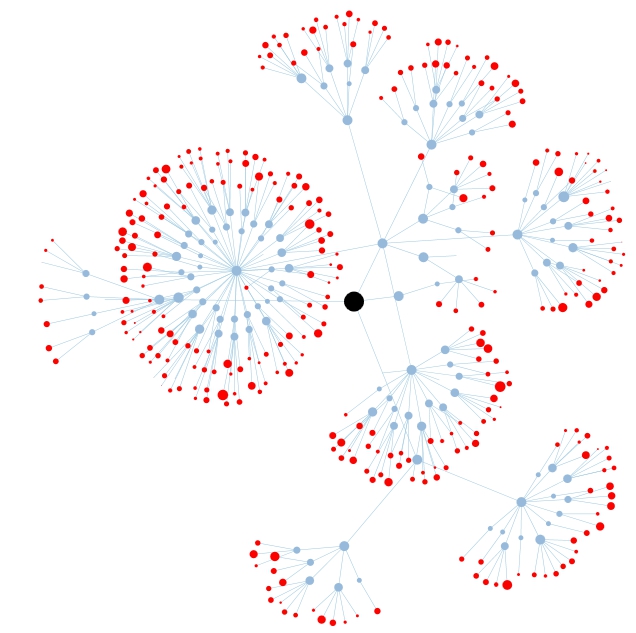

This XML representation of the introduction of a new law at a given time allows a data analysis with the R statistical programming tool, the extraction of its results to a data format (JSON, cf. ECMA 2013) exploitable by the visualization framework D3. We can visualize laws in the form of a hierarchical tree proceeding from the whole body of the text – at the center of the figure – deployed into lower level structural units (Figure 3). This gives us a structural overview of any given law.

The next step of our work consisted in determining a means to measure the growth or regression of any given law over time. What we are interested in is not only the absolute size of the law but, more generally, the degree of difficulty it can represent for a comprehensive overview by individuals deemed to conform to it or to apply it in the case of legal litigation. Beyond this practical aspect, it is also our wish, and our theoretical posture, to understand laws as organic actants (Callon 1986; Latour 1984, 1996), who prosper or regress in a dialectical relationship with the evolution of their “environment” (Ourednik 2010: §2.3.4.1, §2.2.4.2.), i.e. in relation to the context of other laws, superior ( e.g. international) laws, as well as in relation to the social, cultural and economic climate. This posture allows us to speak about growth and regression of laws. Further, considering the dialectical relationship between an actant and its environment, one relatum can be taken as an index (Peirce et al. 1934) of the other. More specifically, observing the evolution of a law allow us to formulate historical hypotheses about the evolution of its environment. The question is what quantitative variables can be used to measure the evolution of a law.

In literature, we can distinguish between two approaches: measured and based on textual statistics partially inspired by information theory and measures based on the spatiotemporal extent of law application.

Among the textual measures, Katz and Bommarito (2013) suggest the use of total text length, average word length, Shannon entropy of word use, depth of the hierarchical structure and density of external references. Höfler and Piotrowski (2011: 87) further consider the structural complexity by observing the number of subunits per structural unit (e.g. paragraphs per article), down to semantic units per sentence, separated by expressions like “whereby” or “with the exception of” etc. Palmirani and Cervone (2014) take a diachronic posture, and propose a comprehensive indicator of dynamic complexity based on the amount and the impact of consecutive amendments to an original law.

Among the extent-based measures, Tribou and Collins (2015) consider the number of USA States in which a given law applies before reaching federal application. Other suggestions imply more extensive approximations. Epstein (1995: 22), for instance, suggests to measure it in terms of the cost of obedience, in other words: “[T]he cheaper the cost of compliance, the simpler we can say the rule is”.

Another question is how to visually render these measurements. In order for our research work to be of consequence in the public sphere, we wish to address three publics: a) researchers, b) jurists, and c) the general public. For each, we have identified specific interests: a) to test the hypothesis of measurability of a historic process and to inspire new fields of investigation, b) to get a synthetic overview of a law, notably in terms of simultaneous or otherwise related amendments; to “identify tough cases [of complex laws] or to help resolve them” (Kades 1996) c) to navigate more easily in the realms of law and to obtain an answer to the question of rising complexity of the leas. From these interests ensue desired qualities of an optimal visualization: a) the hierarchical structure of given law must be visible; the measured quantities must be rendered; the visualization must allow for an animation reflecting the evolution of the measured quantities; b) both hierarchical and transversal (cross-references and thematic) links between elements of law must be renderable; c) the visualization must allow for an understanding of the structure of law for easier access to its elements; it should work as a metaphor of law as an “evolving organism”.

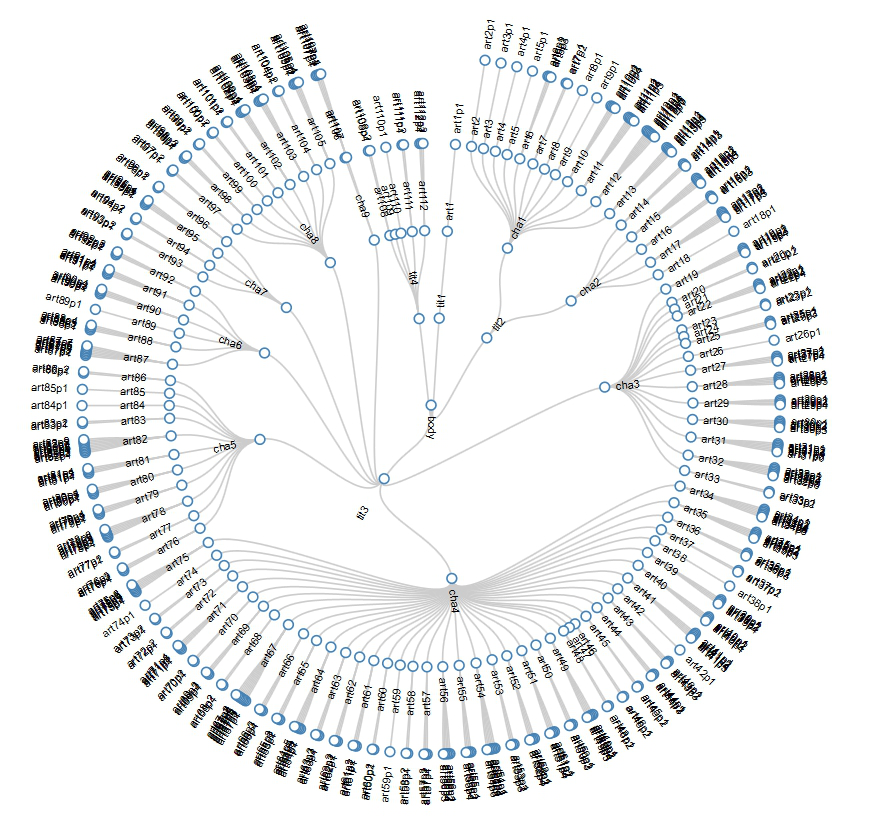

Among possible visualizations, we have considered trees, partition layouts, and circle packing (Ourednik 2013). We have finally opted for a force directed layout as our visualization of choice (Figure 4). In effect, the hierarchical structure of a given law is apparent, without excluding the concurrent visualization of cross-references hardly introducible in tree-structured data. The visualization can easily evolve to reflect historic change (cf. Data Publica 2012). It can also be restructured in order, for instance, to give more weight to thematic, rather than cross-referential transversal links: elements of law thus related become closer in the resulting visualization. Finally from the metaphorical point of view useful for making our theoretical posture understandable to the media and to the general public, the visualization presents a strong analogy with a dendritic organism like a Physarum polycephalum or the mangrove. It thus makes more accessible the description of law in terms of “growth” or “regression”.

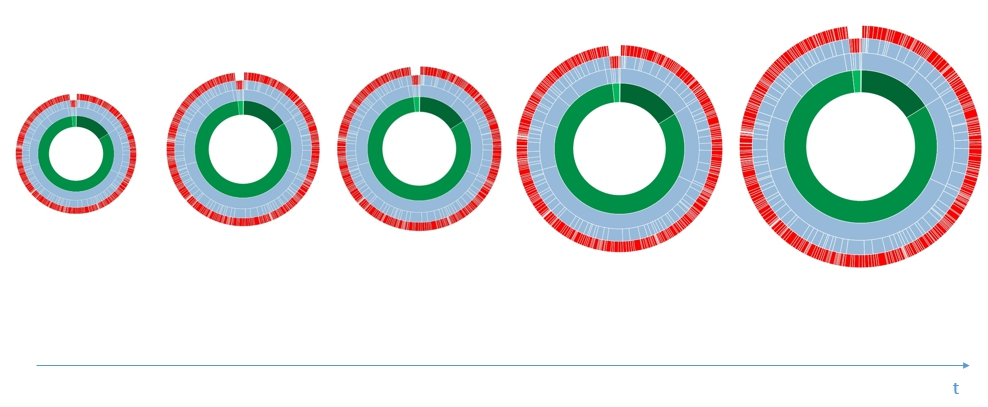

Our second choice visualization is the circular partition tree (Figure 5). Here, transversal links cannot be introduced but the hierarchical structure of law attains better visibility. This visualization also allows for a direct appreciation of the total volume of law and its evolution over time.

At this stage of our research, we have applied quantitative measures based on textual statistics to a static situation, proceeding from an analysis of the French version of the Loi fédérale sur le droit pénal administratif (DPA) from March 22 nd 1974. The hypothesis of measurability of law has thus been verified and we have been able to identify our visualizations of choice. The measurement and visualization method is reproducible for any law at any given time.

Our ongoing work consists in consolidating the data on the evolution of Swiss federal law since 1947 in order to obtain distinct network structures and variable measurements for a fine-grained, week-based, observation of its evolution. Diachronic variable measurements shall be done in parallel on all 3 language versions of the legal texts, and compared, so as to control the robustness of our observations. The Swiss multilingual context offers a unique opportunity for such comparisons.

Visualizations shall be converted in an interactive interface allowing other researches to examine the results and to hypothesize, we hope, innovative explanations of the evolution of the Federal Law. They shall also be made accessible to the general public via the media as an input for the debate about legal complexity in the public sphere.

Fig. 1: Field recognition in the DPA from March 22nd 1974.

Fig. 2: A XML Akoma Ntoso representation the Bundesgesetz über das Verwaltungsstrafrecht from March 22nd 1974 (excerpt).

Fig. 3: Circular tree layout representation of the DPA from March 22nd 1974.

Fig. 4: Force directed layout visualization. Black: body of the DPA from March 22nd 1974. Blue: article with number of contained paragraphs; Red: paragraphs with word lengths.

Fig. 5: Evolution of law viewed in a circle partition layout. size: total amount of text: green : titles, blue : articles and subarticles ; red : paragraphs.